The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently issued draft guidance concerning pediatric research on treatments for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).[i] The document focuses specifically on ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). The goal of the guidance is to offer recommendations for pediatric studies involving drugs that already have a robust development plan for adult participants.[ii] The guidance discusses some general considerations for these diseases and offers drug development recommendations falling under four categories: 1) Study Population, 2) Study Design, 3) Efficacy Considerations, and 4) Safety Considerations. This post will summarize the key points and give advice on how to implement these recommendations.

General Considerations

Treatment for both pediatric UC and CD should focus on resolution and reduction of signs and symptoms of active disease to provide relief to the patient and to reduce the underlying inflammation, thereby reducing the recurrence of symptoms. Given the similarity in disease characteristics between adult and pediatric patients with these conditions, the FDA notes that extrapolation of demonstrated efficacy from well-controlled clinical trials in adults for the same indication is permissible.

Generally, the pediatric study design should be aligned with the adult Phase III program’s design, study population, endpoints, and timing of assessments. The same criteria can be used for both participant populations to define disease activity and endpoints. The FDA recommends the use of modified Mayo Score (mMS) for Ulcerative Colitis and the Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (PCDAI) for Crohn’s Disease. The FDA notes that the PCDAI does have some limitations associated with evaluating intestinal inflammation and recommends assessing inflammation with ileocolonoscopy as an additional assessment.

Study Population

The FDA considers pediatric participants for IBD to extend from two to 17 years of age. For potential participants less than six years of age, the screening process should include an evaluation to exclude monogenic IBD and inherited conditions that present similarly to IBD to exclude these participants prior to enrollment. The IBD diagnosis should be based on documented findings on endoscopy and histopathology. Diagnostic scores from the mMS and PCDAI can be used to evaluate inclusion for UC and CD, respectively.

If the drug is being developed to treat moderate to severe pediatric UC or CD, then the enrollment should encompass participants across the range of severity categories. The protocol should aim to enroll a balanced representation of treatment-naïve participants and participants who have received one or more prior treatments that were inadequate. The FDA also recommends enrolling a participant population that reflects the characteristics of the clinically relevant populations, including race and ethnicity. Sponsors should consider clinical sites with a higher proportion of minorities to ensure recruitment of a diverse population.

When there is preliminary safety and efficacy data for adult participants, the FDA encourages sponsors to consider adding adolescent cohorts (12-17 years old) to ongoing Phase III adult trials. If there are questions about sample size, the sponsor can contact the Division of Gastroenterology (the Division) to discuss this further.

Study Design

The preferred design is a randomized, double-blind study of at least two doses for each age and/or weight-based cohort. This recommendation comes with an important caveat: When the study drug is already approved for use in an adult population, the risks of randomizing pediatric participants with active disease to placebo may outweigh the potential benefits of study enrollment. A placebo arm in such a study would not be appropriate under the subpart D regulations.[iii],[iv] Therefore, sponsors interested in pursuing an active comparator study should discuss the design with the appropriate review division.

The FDA recommends a minimum 52-week blinded treatment period for drugs that are administered chronically. This is needed to assess early efficacy and durability of response over time, and to ensure adequate data concerning safety of longer-term exposure.

The dose selection should be guided by the dose/exposure-response relationship previously seen in adults for the same indication, including data about pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD). A range of doses should be examined to identify an optimal pediatric dose. The guidance notes that a PK lead-in period can be used to confirm predicted exposures for the dose levels. If a lead-in period is used, the protocol should include a planned interim analysis to adjust the dose, if needed. All selected doses should be expected to provide some therapeutic benefit.

The sample size for any study should be large enough to ensure collection of adequate data through week 52 to inform efficacy and safety findings for chronic use in pediatric participants. This should be at least 50-60 participants per treatment arm to ensure enough participants complete the study to provide the data. There should be protocol-defined enrollment targets for each age cohort thereby ensuring adequate data across a range of ages and body weights.

Efficacy Considerations

For both UC and CD studies, the same primary and secondary endpoints used in the adult studies should be followed. The protocol should follow the same timing of scheduled assessments as adult studies to ensure analogously timed results for later comparison.

Considerations for Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis

The primary endpoint should be achieving clinical remission. The FDA recommends centralized reading of endoscopies for evaluating endpoints. Both the endoscopist and central reader should be blinded to treatment assignment when documenting their findings. If there are discrepancies between the endoscopist and the central reader, the protocol should advise how to handle this when conducting the efficacy analysis. The FDA suggests adjudication by a third reader. The FDA also recommends implementing standardized training across sites to minimize bias and standardize readings across sites.

The secondary endpoints should include clinical response, corticosteroid-free remission, endoscopic improvement, endoscopic remission, and maintenance of remission. The maintenance of remission can be evaluated by implementing a re-randomization in the research’s maintenance phase. This will help determine if the therapy can maintain a durable state of remission.

Considerations for Pediatric Crohn’s Disease

The FDA notes that co-primary endpoints may be used for this condition, namely: clinical remission (defined by a PCDAI score of 10 or less) and endoscopic remission. The FDA notes that for some drugs, it may not be possible to achieve complete remission by the end of the study. In these cases, it may be permissible to use endoscopic response as a primary endpoint and endoscopic remission as a secondary endpoint.

As for secondary endpoints, the FDA recommends evaluating clinical response, endoscopic response, corticosteroid-free remission, and maintenance of remission. Like the UC recommendation noted above, the FDA notes that re-randomization during the maintenance phase may be an effective way to demonstrate the therapy can maintain a durable state of remission.

The FDA noted the importance of including analysis of a composite endpoint, namely determining how many participants attain both clinical and endoscopic remission by the end of 52 weeks.

Statistical Considerations for UC and CD Studies

Given the possibility of a study conducted without a placebo control arm, the FDA offers the following suggested comparisons for analysis:

- Comparison of the remission rate in pediatrics on treatment to the remission rate in adults on both active treatment and placebo.

- Comparison of the clinical remission rate in pediatric participants to adult participants on placebo.

- Comparison of the remission rates between dose levels for primary and secondary endpoints.

- Comparison of exposure-response for efficacy between pediatric and adult participants.

Bayesian methods utilizing adult data to support the analysis of the pediatric study should be considered. The FDA notes that comparison to external control arms is permissible. To reduce bias, the analyses should be adjusted to account for participant characteristics at baseline, (e.g., disease severity, concurrent use of corticosteroids, prior biological product use).

The FDA welcomes sponsors to consider developing a new Clinical Outcome Assessment (COA) measure for pediatric participants. If they have a proposed COA, they can contact the Division for review.

Safety Considerations

Research studies should collect adequate data to characterize safety in pediatric participants for the benefit-risk assessment. The safety information obtained from adult studies may assist in this process, but primary safety data from pediatric participants is needed. The FDA may permit the use of real-world data but requests sponsors to contact the Division to discuss this early in the development process. They prefer randomized/blinded data to inform the risk assessment.

Safety analyses should be planned to compare treatment groups with respect to risk. The weaning of corticosteroids should be permitted and standardized in the protocol, ideally at the earliest feasible point following randomization.

The FDA has previously recommended washout periods for prior therapies to be a minimum of five half-lives or undetectable serum level (when available). To promote timely enrollment of pediatric participants and to reduce possible need for corticosteroid bridging therapy, the FDA welcomes sponsors to propose shorter washout periods with supporting rationale to justify it. If there is a shorter washout period, the protocol and consent form should acknowledge the potential increased risk of adverse events (serious infections) and include close monitoring/risk mitigation plans in the scheduled assessments.

If a drug is intended for long-term treatment, there should be data from enough pediatric participants on the to-be-marketed dosing regimen for at least 52 weeks to characterize the safety profile of the drug.

The FDA notes that there may be additional considerations for therapeutic protein products like monoclonal antibodies. They have another guidance covering this topic.[v] In these circumstances, it may be advisable to contact the Division for further discussion.

Discussion of Pediatric Extrapolation and Use of Placebo

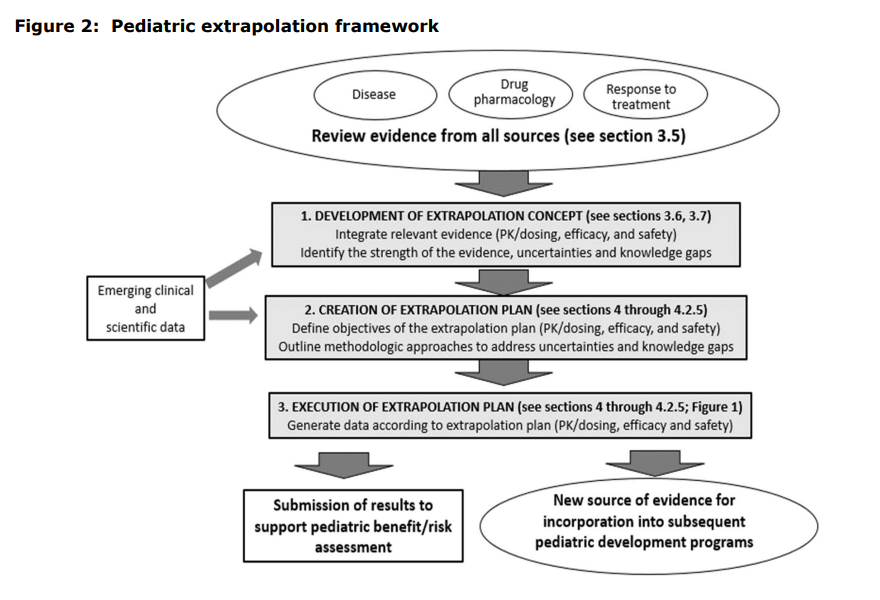

This guidance makes recommendations on study design and conduct based on the concept of pediatric extrapolation. In August 2024, the International Council for Harmonization (ICH), working in collaboration with the FDA, issued final guidelines discussing this concept.[vi] Pediatric extrapolation assumes that the course of the disease and the expected response to the investigational product should be sufficiently similar in adult and pediatric participants such that efficacy established in adults can be extrapolated to the pediatric population. Additionally, if efficacy is established in one pediatric population (e.g., adolescents), efficacy may be extrapolated to younger children. Although this concept generally applies to efficacy, some extrapolation of safety may be reasonable, depending on what safety data has previously been collected. The level of data needed to use an extrapolation approach depends on the level of certainty on similarity and whether any knowledge gaps exist. The amount of data needed will vary based on the condition and how it manifests in adults compared to children. See figure below from the ICH guidance.[vi]

For pediatric clinical trials for UC and CD, collection of some efficacy data is recommended, but the comparator is generally an active treatment rather than placebo. However, a smaller sample size is acceptable when adult data can be applied. Aligning the adult and pediatric endpoints is essential to allow efficacy comparisons between the adult and pediatric study results. Usually, PK and PD data are needed in the pediatric study to compare exposure/response (E/R) in children to that in adults and to establish pediatric dosing. Differences in E/R can also be used to determine efficacy; if one dose level performs better than another, that information can support an efficacy claim.

Pediatric extrapolation is reinforced by the concept of Scientific Necessity outlined in the guidance, “Ethical Considerations for Clinical Investigations of Medical Products Involving Children.”[iv] “Children should not be enrolled into a clinical investigation unless their participation is necessary to answer an important scientific and/or public health question directly relevant to the health and welfare of children.” Clinical investigations in children evaluating efficacy may not be necessary when pediatric extrapolation applies, or studies may be streamlined to reduce the burden on children when enrolled in clinical trials depending on the level of data needed to identify any uncertainties when applying pediatric extrapolation.

Of note, this guidance does not recommend a placebo-controlled trial in pediatric patients. Even when pediatric extrapolation is not applicable, it may be inappropriate to conduct a trial in children using a placebo. If placing the child on placebo places the child at a significant risk of disease progression during a clinical trial, especially when there are alternative treatments available, it may not be ethical to use a placebo. [iv] [vii]

Conclusion

The FDA has issued a comprehensive draft guidance to assist investigators and sponsors in developing pediatric studies for IBD, specifically UC and CD. The guidance outlines the requirements for clinical trials and addresses: 1) Study Population, 2) Study Design, 3) Efficacy Considerations, and 4) Safety Considerations. Given the similarity in disease characteristics between adult and pediatric participants with UC and CD, the FDA notes that pediatric extrapolation of demonstrated efficacy from well-controlled clinical trials in adults for the same indication is permissible. However, some collection of data on efficacy in pediatric studies is recommended. Alignment of scheduled assessments and study endpoints from adult studies is important to allow comparison between pediatric and adult study results and apply pediatric extrapolation. Given the duration of the pediatric studies (52 weeks) and the availability of alternative treatments, using a placebo in pediatric studies for IBD is not considered ethical since withholding therapy would expose children to unnecessary risks without any clinical benefit.

References:

[i] Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Developing Drugs for Treatment (July 2024), available https://www.fda.gov/media/180126/download.

[ii] The FDA noted that sponsors seeking to develop drugs for pediatric subjects only should contact the Division of Gastroenterology (the Division) to discuss their plans.

[iii] Subpart D risk categories, 21 CFR 50.52, et. seq. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=50&showFR=1&subpartNode=21:1.0.1.1.20.4

[iv] Ethical Considerations for Clinical Investigations of Medical Products Involving Children (September 2022), available https://www.fda.gov/media/161740/download.

[v] Immunogenicity Assessment for Therapeutic Protein Products (August 2014), available https://www.fda.gov/media/85017/download.

[vi] E11A Pediatric Extrapolation (August, 2024), available https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/ich-guideline-e11a-pediatric-extrapolation-step-5_en.pdf.

[vii] ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline Choice of Control Group and Related Issues in Clinical Trials E10 (July 2000), available https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/E10_Guideline.pdf.