Introduction

The topic of diversity continues to be a focus in the clinical research sphere. As a result, there has been some speculation as to how certain information, such as race and ethnicity data, would ultimately be recorded when reporting to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The Guidance discussed herein titled, “Collection of Race and Ethnicity Data in Clinical Trials and Clinical Studies for FDA-Regulated Medical Products” (hereafter FDA Guidance), provides specifics about the minimum expectation in the reporting of minority groups involved in clinical research and highlights recommended best practices for sponsors.

After the January 2024 publication of the FDA Guidance, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) revised their Statistical Policy Directive No. 15 (Policy Directive 15), which the FDA Guidance uses to describe the racial and ethnic categories. The FDA is in the process of updating their racial and ethnicity categories to match the updated Policy Directive 15, but otherwise the FDA Guidance remains applicable.

Standardized Terminology and Policy Directive 15

FDA recognizes the practical challenges in achieving the appropriate enrollment of diverse populations in clinical trials. The FDA Guidance introduces new standardized terminology for race and ethnicity to establish that the submissions to FDA report those diverse groups adequately.

Their recommended approach is based on the OMB’s Policy Directive 15, which was developed in accordance with section 4302 of the Affordable Care Act; the Health and Human Services (HHS) Implementation Guidance on Data Collection Standards for Race, Ethnicity, Sex, Primary Language, and Disability Status; and the Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA) Section 907 Action Plan.1

OMB’s Policy Directive 15 was initially developed in 1977 to provide consistent data on race and ethnicity.2 In early 2023, OMB announced that a formal review of the 1977 Directive would be taking place. In March 2024 the Policy Directive 15 was revised.

A Basis for the Collection of Racial and Ethnic Data

FDA cites instances in which the ethnic or racial background of a clinical trial participant may play a critical role in different responses to a drug or medical device. In particular, genetics, metabolism, skin pigmentation, or even socioeconomic status are factors to take into account when considering efficacy, safety, or pharmacokinetics. In this framework, ethnic or racial background becomes an important data point for researchers.

Of note, in Policy Directive 15, OMB took the stance that the recommended race and ethnicity categories were not scientifically based designations, but instead were categories that describe the sociocultural construct of society. This perspective is particularly powerful as it applies to the resulting categories that FDA recommends for trial sponsors.

Revised OMB Policy Directive 15

On March 29, 2024, revisions to OMB’s Policy Directive 15 were published in the Federal Register.3 A major change in Policy Directive 15 was to eliminate the two-part ethnicity questions previously used to have a combined race and ethnicity question. Policy Directive 15 now uses a single question format, as public comments stated the two-question structure was confusing. However, in response, some commented that the single-question format with a combined race and ethnicity question joined two very different concepts and even implied that Hispanic or Latino is a “race.”

Ultimately, the flaws in the two-question format were noted by the responses provided in the previous decennial census. The 2020 census showed that 43.5 percent of those who self-identified as Hispanic or Latino either did not report a race or were classified as “Some Other Race” alone. Twenty-three million people answered in this manner, so this “non-response” was interpreted as a failure of the question which was not providing options but hindering them.

One additional topic discussed in the revised OMB’s Policy Directive 15 is on the topic of what constitutes “minimum collection of race and ethnicity data.” Part of the concern is that although the more data collected the more value derived, in some cases, the additional burden would outweigh the potential benefits of collecting detailed data. Ultimately, agencies are required to collect the detailed categories described in that Federal Register Notice as a default.

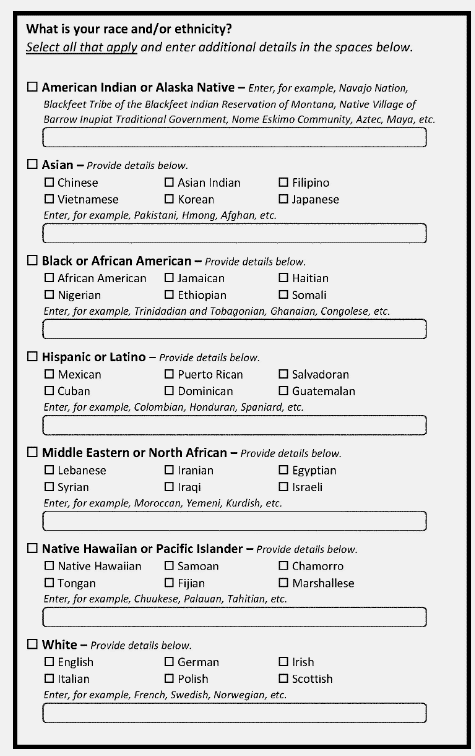

The new set of minimum race and/or ethnicity categories are:

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Asian

- Black or African American

- Hispanic or Latino

- Middle Eastern or North African

- Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- White

The figure above is from the Federal Register’s revised OMB document. It is an example of how explanatory/write-in boxes and minimum categories can be used together to effectively capture the most details about a person or group. Additionally, there are multiple detailed checkboxes to aid in self-identification.

Anticipated Setbacks

FDA bases most of the logic for their current Guidance on the Policy Directive 15 from 1977. However, challenges continue to remain for sponsors and researchers who find themselves in regions where this basic application of rules just won’t be sufficient. FDA encourages those researchers to reach out to the division of the FDA appropriate for the research they are conducting. The remaining question is: Will this guarantee that race and ethnicity are both adequately captured in a landscape that is becoming increasingly diverse?

FDA has continued to remain consistent in what is communicated to the clinical research community with a goal of race and ethnicity data being more accurately recorded in research. Without an ever-changing standard, the possibility for consistency in how data is collected is more feasible. Furthermore, it is important to remember that accurately capturing this data aims at resolving a bigger issue: the lack of diversity in clinical research at large. If there is work to be done, it principally lies in finding the best method to capture race and ethnicity data accurately, every time, in support of a more inclusive research sphere.

The Greater Problem: Diversity in Clinical Trials and What You Can Do Now

Properly recording diversity in clinical trials will be the product of the enrollment of a diverse group of individuals in research. Its value cannot be forgotten or set aside. However, understanding the goals early on, making sure study teams are supported and guided to correctly collect this information, and verifying it early in the trial’s progression are all recipes for success.

Site staff may be instrumental when attempting to enroll a more diverse group of participants in clinical research. For example, site staff and principal investigators who “look like” the participant and “speak their first language” are likely to bridge the trust gap. Additionally, the incorporation of translated advertisements into common submission materials is also a major step forward for sponsors to allow potential trial participants that do not speak English as a first language to have the same access to clinical trials. Adding sites that are geographically dispersed may have the potential to reach a greater proportion of more racial and ethnic diverse populations. And finally, not forgetting that sponsors can and should reach out to cherished members and leaders of the community to build trust in areas where there may be trust gaps.

Recommended Best Practices for Sponsors

Sponsors are encouraged to plan early and know when it is time to reach out for help from the FDA. In particular, if the sponsor is aiming to collect certain diversity numbers, sponsors must be sure to have a plan in place to collect that data from the onset. If it is known that diversity data will be collected, it must be clear at which point in the process that data will be collected and there must be an intention to collect that data.

On the other hand, it is important for sponsors to empower teams at a site level to collect this diversity information as early in the clinical trial process as is possible. This usually means data collection at pre-screening or screening. To differentiate, “pre-screening” refers to activities that take place prior to obtaining informed consent. These activities take place after a potential participant expresses interest in the study and initial eligibility questions are asked of the participant to determine if they meet the criteria to be enrolled. On the other hand, “screening” refers to activities which take place after obtaining informed consent.

If sponsors track diversity data early in a clinical trial, it is possible to reset the mark if necessary. In particular, if diversity data are being collected at pre-screening or screening and target numbers are not being met, then there is time to modify goals to reach the target diversity numbers. However, waiting until the enrollment period is closed to see if diversity goals are met could be problematic, as there would be no opportunity to correct.

Conclusion

Reaching diversity goals may appear to be a tall order. However, early planning may alleviate the potential for later pressures. Should any issues be anticipated in reaching diversity goals, strategies or materials may be timely modified with the end goal of capturing a more diverse population. Sponsors and sites must remember the value and need for these diverse populations in the first place. The entire rationale behind a more diverse population is to ensure that new drugs or devices are as safe and effective for all of those in our collective society and not just one segment of the population. Sponsors should work together with sites to inspire and empower them in the early recruitment of diverse populations.

References

- Collection of Race and Ethnicity Data in Clinical Trials and Clinical Studies for FDA-Regulated Medical Products, https://www.fda.gov/media/175746/download; OMB Statistical Policy Directive No. 15, Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity (Policy Directive 15) (October 30, 1997), available at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/omb/fedreg_1997standards. HHS Implementation Guidance on Data Collection Standards for Race, Ethnicity, Sex, Primary Language, and Disability Status (October 31, 2011), available at https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/hhs-implementation-guidance-datacollection-standards-race-ethnicity-sex-primary-language-disability-0.

- Flexibilities and Best Practices for Implementing the Office of Management and Budget’s 1997 Standards for Maintaining, Collecting, And Presenting Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity (Statistical Policy Directive No. 15) https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Flexibilities-and-Best-Practices-Under-SPD-15.pdf.

- Revisions to OMB’s Statistical Policy Directive No. 15: Standards for Maintaining, Collecting, and Presenting Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity (March 29, 2024), available at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/03/29/2024-06469/revisions-to-ombs-statistical-policy-directive-no-15-standards-for-maintaining-collecting-and.

Ensure Diversity in Your Next Trial

Diversity is not only the right thing to do: It’s good business. You want your clinical trial population to reflect your product’s future consumers. We can help. WCG’s DEI solution has defined policies and processes to engage, educate, enroll, and retain diverse populations in clinical trials.

Contact WCG today by filling out the form below.