The New World of Depression Treatment

In 2019, the treatment of depression changed forever, the result of decades of research by academia, industry and government agencies.

What happened? The US FDAapproved esketamine. It was a landmark moment: Approval of this new rapid-acting antidepressant formulated for intranasal use marked the beginning of a new era.

At present, depression—and major depressive disorder in particular—affects a startlingly high percentage of the population. In the United States, the estimated lifetime risk of a major depressive episode is almost 30%.1 Roughly 30% of U.S. adults with depression reported moderate or extreme difficulty with work, home and social activities due to depression.2 Major depressive disorder (MDD) is the third-leading cause of disability worldwide.3

Compounding these public health challenges is the fact that available treatments have thus far been inadequate; about a third of Americans with MDD aren’t receiving any treatment, while only a little more than half reported using medication.4,5

To fully understand the reason this class of medications holds such promise for the future, it helps to understand the history of depression pharmacotherapy.

Millenia of Melancholia

Depression (or melancholia) has been recognized as a clinical disorder for more than 2,000 years. Hippocrates attributed it to the excess of black bile, one of the four basic humors – the others were blood, yellow bile and phlegm. In the centuries that followed, physicians, scholars, philosophers, among many others, referenced the condition in their works.6

As the 20th century progressed, the advent of modern psychopharmacology brought together rigorous methods and serendipitous discoveries. In the 1950s and 1960s, clinical and pharmaceutical research into depression treatments boomed. Antidepressant drug development began with the discovery of monoamine oxidase inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants and moved into selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).7

Researchers stumbled on the first pharmacological antidepressant: In the 1950s, the FDA approved Iproniazid, a monoamine-oxidase inhibitor, as a tuberculosis therapy. However, physicians began using it off-label to treat patients with depression. The FDA approved imipramine for the treatment of depression in 1959, making it the first tricyclic antidepressant.8

It wasn’t until 1965 that depression therapy underwent the gold-standard of research: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. That study compared imipramine, phenelzine, electroconvulsive therapy and placebo.9,10

In the late 1960s, researchers found evidence suggesting a significant role of serotonin in MDD. In 1987, fluoxetine became the first FDA-approved selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.11 Until the recent breakthrough with esketamine, SSRIs represented one of the most significant medical discoveries of the last half century.

SSRIs have been successful for many people with depression, but they can take four to six weeks to have any effect. More concerning, they have a high non-response rate. It became clear that serotonin didn’t fully explain depression, and the drugs targeting serotonin couldn’t help everyone suffering with the disease.

Something had to change. Researchers turned their attention to other neurotransmitters such as GABA and glutamate–already known to play a role in seizure disorders and schizophrenia.12

Enter ketamine.

Above and Beyond Serotonin

Scientists and clinicians have known about ketamine’s antidepressant properties for some time, beginning with studies at Yale University and the National Institute of Mental Health. It’s been used in clinical practice as an anesthetic since the 1960s,13 and many doctors have used it off-label to treat depression.14

But, until very recently, no one sought regulatory approval for it as an antidepressant. That approval changed everything.

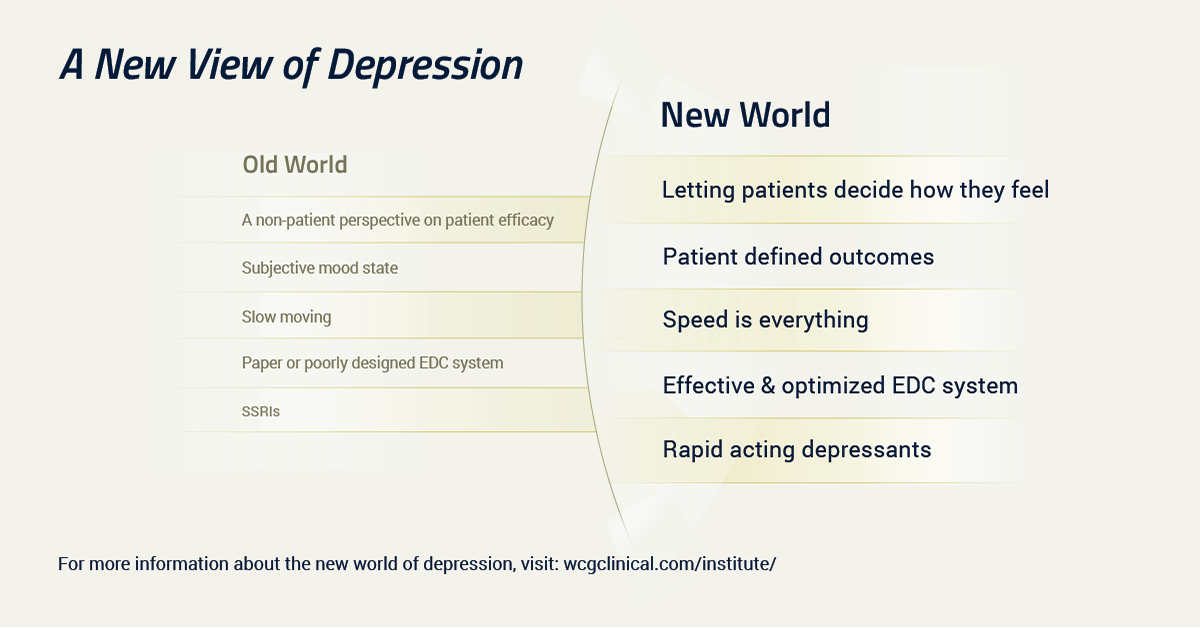

As we suggested earlier, there are now two eras in the psychopharmacology of depression. There is the pre-esketamine era—everything that came before FDA’s approval—and everything that comes after.

Until 2019, every antidepressant approved by the FDA targeted the biogenic amines, including dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin. Ketamine—and now, esketamine—work on an entirely different mechanism of action. It’s an antagonist for the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. It triggers a surge in glutamate production, which makes the brain more adaptable and able to create new pathways.15

This novel mechanism of action likely underlies the ultra-rapid relief it provides. Traditional-acting antidepressants can take weeks to months to see full therapeutic effects of treatment – an especially salient consideration considering the rising suicide rate in the United States. Esketamine, in contrast, often acts within hours, and it’s effective in many patients for whom nothing else has worked.

The difficulty of adequately treating treatment-resistant depression coupled with its crippling effects make the success in esketamine clinical trials all the more groundbreaking, potentially transforming the treatment and remission for patients diagnosed with depression.

But this is just the beginning.

Unexplored Territory: New Domains, New Tools

We’re on the cusp of a new era in psychopathology and psychiatry. As more ketamine-like, rapid-acting antidepressants progress through different stages of research, we’ll gain a better understanding of the neurobiology of depression. However, we’ll need to develop better tools to capture outcomes and patient experience.

A new era in research and treatment requires new tools. Each treatment breakthrough in psychiatry typically brings new insights into measurement and assessment. That will be essential for rapid-acting antidepressants.

At present, we have a limited choice of outcome measures. The MADRS, the HDRS, BDI and the other tools we’ve long used were not built to capture treatment at the speed with which these new treatments work.

We need new tools that capture not only clinical outcomes, but also the patient experience. We cannot talk about antidepressant efficacy without talking about what matters to patients.

Addressing core symptoms that have been the focus of clinical attention in past decades is no longer adequate. Entire domains of psychopathology remain to be more fully explored, including anhedonia, cognition and functional recovery.

While the new frontiers of neurobiology that ketamine and esketamine have opened up are promising, perhaps the area crying out for the most innovation lies elsewhere: the patient experience and the patient voice. How do we better include patients, patient advocates, families and other stakeholders in development of new treatments? How do we create a true dialogue rather than the monologue that has characterized the history of drug development so far? How can we make sure everyone benefits?

We all must rise to that challenge on the cusp of this new era.

References

1. Park LT, Zarate CA Jr. “Depression in the Primary Care Setting.” N Engl J Med. 2019 Feb 7;380(6):559-568. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1712493. Updated Feb. 2019

2. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief No. 303, February 2018

3. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Seattle, WA: IHME, 2018.

4. Hasin, DS, et al. “Epidemiology of Adult DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder and Its Specifiers in the United States.” JAMA Psychiatry, 75(4), 336. (2018)

5. National Institute of Mental Health: Major Depression. Updated Feb. 2019

6. Telles-Correia D, Marques JG. “Melancholia before the twentieth century: fear and sorrow or partial insanity?” Front Psychol. 2015 Feb 3;6:81. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00081.

7. Hanrahan, C. New, J. “Antidepressant medications: The FDA-approval process and the need for updates.” Mental Health Clinician 2014

8. Hillhouse TM, Porter JH. “A brief history of the development of antidepressant drugs: from monoamines to glutamate.” Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;23(1):1–21.

9. Khan, A. et al. “The conundrum of depression clinical trials: one size does not fit all.” International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 33(5), 239 (2018)

10. Khan A, Detke M, Khan S et al. “Placebo response and antidepressant clinical trial outcome.” J Nerv Ment Dis 2003;191:211‐8

11. Hillhouse TM, Porter JH. “A brief history of the development of antidepressant drugs: from monoamines to glutamate.” Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;23(1):1–21. d

12. Chen, J. “How New Ketamine Drug Helps with Depression,” Yale Medicine, March 21, 2019

13. Li, L & Vlisides, P. E. (2016). “Ketamine: 50 Years of Modulating the Mind.” Front. Hum. Neurosci., 10. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00612

14. Wilkinson ST, Sanacora G. Considerations on the Off-label Use of Ketamine as a Treatment for Mood Disorders. JAMA. 2017 Sep 5;318(9):793-794. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.10697.

15. Abdallah CG, et al. “Ketamine’s Mechanism of Action: A Path to Rapid-Acting Antidepressants.” Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(8):689–697