Introduction

On August 21, 2024, the International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceutical Use for Human Use (ICH) finalized Guideline E11A on Pediatric Extrapolation. The purpose of the guideline is to provide recommendations and facilitate global harmonization for the use of pediatric extrapolation to support the development and approval of pediatric medicines. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) adopted this guideline as FDA guidance in December 2024. The guidance contains additional information specific to pediatric extrapolation and builds on information in the ICH E11 (R1) guideline “Clinical Investigation of Medical Products in the Pediatric Population: Guideline and Addendum,” which was also adopted by the FDA as guidance. By exploring the ICH E11A guideline, this piece defines pediatric extrapolation and the regulatory expectations, describes ethical considerations, and shares study design adaptations for pediatric extrapolation.

Background for Pediatric Extrapolation

Pediatric extrapolation is a concept used in drug development to apply the efficacy and safety data obtained from adult clinical trials to pediatric populations. This approach assumes that the course of the disease and the response to the investigational drug are sufficiently similar in both adults and children. It also assumes that children will benefit from exposure to the investigational drug so that studies in children will offer sufficient prospect of direct benefit to justify the risk. By using pediatric extrapolation, researchers can reduce the need for extensive clinical trials in children, thereby accelerating the availability of safe and effective drugs for pediatric use.

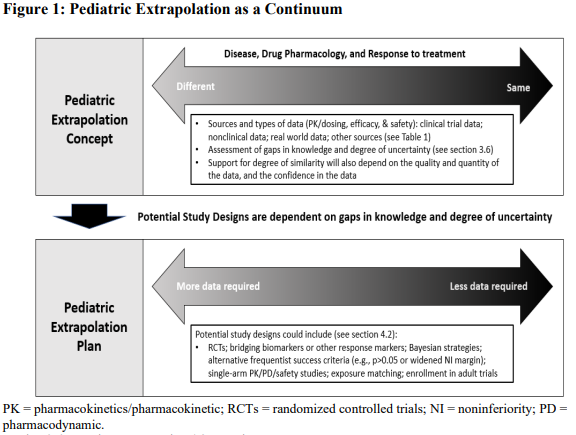

In the past, specific categories, full, partial, and no extrapolation, were used to describe the level of extrapolation allowed for an indication or condition. E11A states that extrapolation occurs on a continuum. The degree upon which similarity is determined is accomplished by a multidisciplinary review of the strength of the evidence, the confidence in the data available, and any remaining knowledge gaps. The amount of information needed will vary based on the condition and how it manifests in adults compared to children. See Figure 1 below from the FDA guidance.

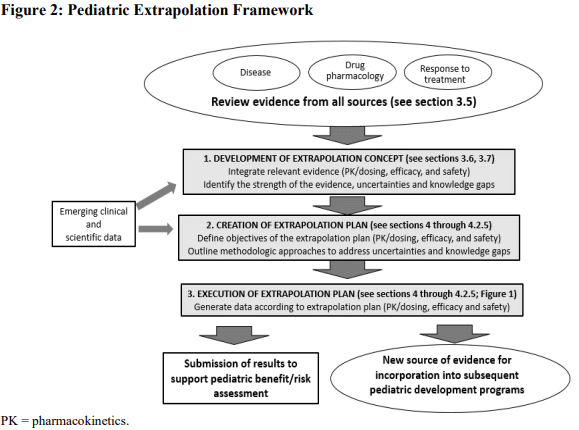

The guidance also includes a framework for using extrapolation within a pediatric drug development plan that builds on figure 1. As new clinical and scientific data is collected for a condition or disease, the extrapolation plan can evolve over time. As gaps in knowledge are addressed, less data may be required when executing the pediatric extrapolation plan. This allows the framework to be modified as new information is collected. See figure 2 from the guidance below for a description of the framework.

Inclusion of Pediatric Participants in Adult Clinical Trials

If researchers are confident that pediatric extrapolation can be applied to the development of a drug, it may be possible to include children in the adult drug development program before the drug is approved for adult use. Adolescent participants are often considered first because additional information to support dosing may not be necessary. In most cases, the pharmacokinetics (PK) in adults and adolescents are similar. Often, the barriers to enrollment of adolescents in adult trials can be as much operational as scientific and ethical.

Scientific considerations include aligning the primary endpoint to allow pooled analysis of data and using similar safety assessments to allow safety comparisons. Ethical considerations include whether a placebo control is appropriate for pediatric participants. Operational issues include the added complexities of parental permission and adolescent assent, and whether sites that enroll adults have access or the capability to enroll =adolescent participants. Younger children may be included in adult studies, but often because of differences in dosing and varying safety concerns, it may be more expeditious to conduct a separate pediatric study, unless the overall study population is so small (e.g., rare disease clinical trials) that separate adult and pediatric studies may be difficult to conduct.

The Roles of Modeling and Simulation

Modeling and simulation play a significant role in supporting a pediatric extrapolation plan and in pediatric drug development in general. Modeling and simulation may be used, for example, to evaluate similarity of disease and response to therapy, inform study design, develop dosing recommendations, and anticipate the effects of the drug in the relevant population. It can also be used to confirm the underlying extrapolation concept when the pediatric study is completed.

Appropriate dose selection is important in pediatric studies, but separate PK/pharmacodynamic (PD) studies may not be necessary. Often PK data can be collected within the pediatric efficacy study or as a lead in to a pediatric study to fine tune the dose, or modeling and simulation can be used to predict a dose if the effect of the disease on the PK is known. For example, in cases where the drug has already been studied in a pediatric population for another indication and the exposure is known or when there is exposure data in adults for the indication and matching exposure data for another indication in a pediatric population. Occasionally dose ranging data may be required as part of an extrapolation plan, such as in cases where there is uncertainty about disease similarity and/or response to treatment, if there are potential age-related differences in target expression, or for locally acting drugs where there is no correlation between therapeutic response and systemic drug exposures.

When designing the adult drug development program, it is important for sponsors to consider the pediatric program when it comes to what biomarkers and endpoints are included in adult studies. For example, if an endpoint or biomarker may be relevant to the pediatric program, it could be included in the adult study and then utilized in the pediatric program to support efficacy. If there are differences in endpoints, then an evaluation of relationships of the endpoint in the adult population compared to the pediatric population should be conducted to support the pediatric program. For example, a six-minute walk test may not be appropriate for pre-ambulatory pediatric participants, so other measures should be explored that may be used in the pediatric study. If the endpoint in the pediatric study differs from that in adult studies, then the acceptability of the use of the endpoint in the extrapolation plan should be discussed with regulatory authorities while studies are in the planning stages.

If safety will be extrapolated, it is critical to provide strong justification as to why the safety data from the reference population (usually adults) is applicable to the pediatric population. Safety data collection should address the scientific questions to be answered, identify any knowledge gaps, and address any uncertainties that exist. Selected safety issues might need to be evaluated in a pediatric study that are not addressed with the existing safety database to support the safety of the drug in the pediatric population under study. There also may be cases where the existing safety data is sufficient to support the use of the drug in the pediatric population and no further safety data will need to be collected.

Study Design & Extrapolation Plan

The type of studies required when pediatric extrapolation is utilized can vary depending on the drug development program. As noted in figure 1, there is a continuum when extrapolation is considered based on the confidence in the similarity of disease and response to treatment. Studies may range from matching effective and safe exposures in the adult population to the pediatric population, to PK/PD studies when exposure matching alone is not sufficient to establish a dose, to studies evaluating efficacy. Embedded exposure matching or PK/PD components may be included in efficacy studies as noted above. Whatever study design is chosen, the extrapolation plan should be discussed with regulatory authorities and based on the extrapolation concept.

When required, efficacy studies within an extrapolation plan may vary. Often, additional efficacy information is needed to support use of the drug in the pediatric population since the effect of treatment on outcome in the pediatric population could be different than that in adults. However, it may be possible to utilize Bayesian techniques in the pediatric population to reduce the number of pediatric participants needed to address the scientific question. Single arm studies may be appropriate when considered sufficient to establish efficacy or when a suitable control arm does not exist. When a single arm study is thought to be sufficient, prespecified criteria should be established that define how the primary efficacy objective will be evaluated.

Studies that utilize external control, such as relevant existing control arms from other studies or real-world data (RWD), can also be considered under an extrapolation plan. In the case where an external control is used, statistical methods should consider the potential for bias and confounding when comparing data.

Finally, controlled studies may be needed in some situations to establish efficacy, but because some degree of extrapolation is utilized, the study design may be different from adult studies. It may be difficult to conduct placebo studies in the pediatric population if there is some expectation based on extrapolation that the drug will be effective in children. Additionally, when non-inferiority study designs are used, the study may be powered to meet a relaxed success criterion—or the non-inferiority margin widened compared to the adult program—since the adult data may be relied upon to some extent based on the extrapolation concept. It is essential to affirm that the point estimate of the treatment effect in the pediatric study does not result in questions regarding inferiority.

Conclusion

In summary, the FDA’s acceptance of the ICH E11A Pediatric Extrapolation Guideline marks a significant advancement in the harmonization of pediatric drug development. The guidance describes how pediatric extrapolation can be utilized when designing studies for pediatric drug development programs. This should expedite the availability of safe and effective medications for children while minimizing the need for extensive clinical trials. This collaborative effort underscores the importance of innovative approaches in addressing the unique challenges of pediatric medicine and ensuring that children receive timely access to essential therapies.

Do you have additional questions about pediatric participants in your clinical study or other ethical review questions? WCG’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) experts are here to support you in navigating all the complexities of trial development and reviews, including pediatric extrapolation and more. Please complete our form below to get in touch today.

Don't trust your study to just anyone.

And we’re the best for a reason. Experience the WCG difference starting with a free ethical review consultation. We’re here to help you streamline, alleviate, and accelerate.