On April 4, 2024, the National Institutes of Health released a finalized amendment to the NIH Guidelines for Research Involving Recombinant or Synthetic Nucleic Acid Molecules (NIH Guidelines). While the amendment was issued primarily to cover gene drive research with organisms unlikely to be tested in a clinical setting any time soon, it also comes with a change in scope that will impact clinical trials going forward.

As noted in the Federal Register notice, the amendment goes into effect September 30, 2024. As of that date, certain genetically engineered cellular therapies will be subject to the NIH Guidelines and biosafety requirements outlined therein. Read the full post below for additional details from our experts and learn about what the changes could mean for your research!

CRISPR and gene editing technologies have been in the news due to their transformative potential in clinical drug development. All new technologies require careful assessment of risk and benefits—and the NIH has recently issued new rules that expand the requirements for biosafety review of clinical trials involving intentional modification of the human genome.

Originally released in 1976, the NIH Guidelines for Research Involving Recombinant or Synthetic Nucleic Acid Molecules (NIH Guidelines) serve as the foundation of biosafety-focused oversight of research involving recombinant or synthetic nucleic acids (rsNA). It also establishes the role of the Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC) in providing local oversight of such research. Although the NIH Guidelines were originally written with non-clinical laboratory research in mind, they also apply to human gene transfer (HGT) research, wherein rsNA or rsNA-containing products are administered to research participants.

Since their creation, the NIH Guidelines have been updated several times in response to scientific advances and to align with best biosafety practices outlined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other biosafety-focused organizations. In 2012, the NIH Guidelines were updated to apply to certain research with oligonucleotides that was previously exempt. This change expanded the definition of HGT research to include research using nucleic acids that are able to replicate, be transcribed, translated into protein, and/or integrate into the host genome. At the time this change was implemented, methods used to deliver rsNA to cells or research participants typically involved the use of viral vectors that were subject to the NIH Guidelines. Since then, however, certain genetic engineering technologies (e.g., CRISPR-based gene editing) have advanced to the point where cellular genomes can be edited without using viral vectors or any other materials subject to the NIH Guidelines and without integration of rsNA into the chromosome. Practically speaking, this means that certain genome editing products and genome-edited cells can be administered to research participants without IBC review. For example, two trials testing genetically identical genome-edited cell therapies – one engineered with a viral vector, and one without – can differ in their IBC review requirements because of how the cells were modified rather than what they have become. Lack of biosafety oversight for such products can have profound consequences, the most notable of which include potential exposure of clinical staff to products capable of irreversibly modifying their genomes.

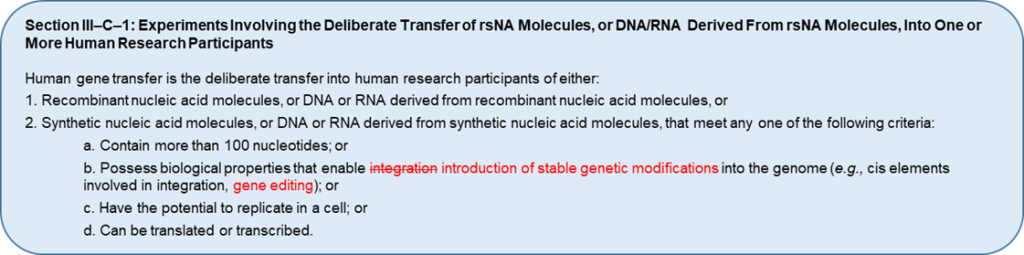

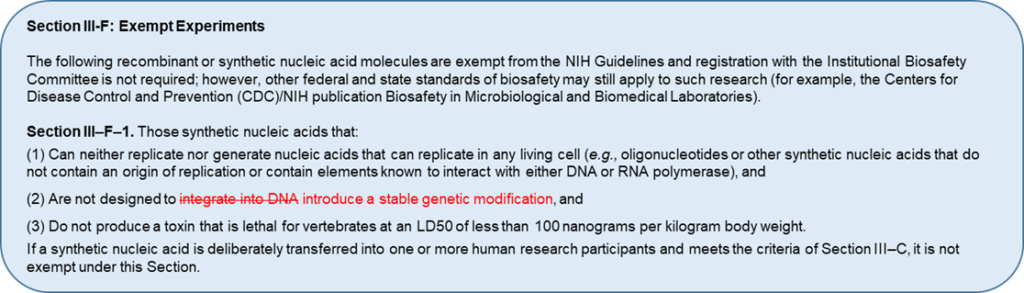

In August 2023, the NIH Office of Science Policy requested input from biosafety experts and the public on proposed revisions aimed at closing this gap in oversight. Specifically, the NIH is proposing to revise the definition of HGT research and exemption criteria described in Sections III-C-1 and III-F-1 of the NIH Guidelines (see images). If implemented, these changes would broaden the definition of HGT to include new gene editing and genome-modified products. These changes would also affect HGT trial sponsors and investigators, who would face new compliance requirements, as well as IBCs, who would be tasked with overseeing new types of HGT research.

It is unknown when these changes would go into effect if they are ultimately adopted. It is also unclear whether the proposed changes would only apply to new research or if investigators would be required to seek retroactive IBC approval for ongoing research. In the interim, investigators, institutions, and clinical trial sponsors may consider voluntarily requesting IBC review of research that would require it in the future if these changes are adopted. Nonetheless, IBCs and investigators conducting HGT research should ensure that the research is conducted safely and in the best interest of clinical staff and the general public. This will be particularly important for maintaining public confidence in science and clinical research as new genetic engineering technologies enter the clinical setting.

Don't trust your study to just anyone.

Partnering with WCG puts it in the best hands. We’ll help you every step of the way, from timeline and enrollment dates to qualification of prospective sites to document preparation and distribution. Experience the WCG difference starting with a free IBC services consultation.